Eyes on the Prize: A Look at the 2024 Nobel Prize-Winning Research that Attempts to Explain Why Some Nations Develop and Others Don't

Andrew Stein '27

Imposing metal slats and coils of barbed wire form the boundary between International Street in Nogales, Arizona, and Calle Internacional in Nogales, Mexico. Geographically and culturally, the two cities have many similarities. But on the ground, several stark contrasts emerge. Residents of Nogales, Mexico, have a roughly fifty-fifty chance of graduating high school compared to over 70% for the Arizona city, poverty rates are 35% higher, and annual household income in Sonora is one-third that of Nogales, Arizona.

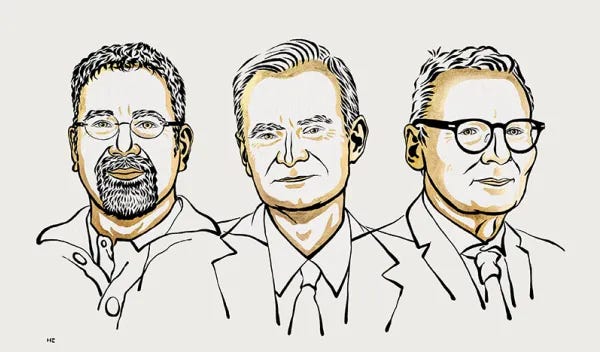

This comparison typifies the Nobel Prize-winning research of Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson. Over two decades in the making, the trio’s research aims to explain why some countries are more developed than others by examining their colonial histories. The trio’s exploration into the topic began with their 2001 paper “The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation” and was expounded in Johnson and Acemoglu’s 2013 book Why Nations Fail.

Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson propose that “extractive” European powers set their colonies up for failure and inhibited their development as independent states. On the other hand, European powers that established “inclusive” institutions in their colonies created successful economic and political systems. For example, Spain’s colonization of Mexico involved rigid imperial control and focused on extracting mineral wealth, often through violence. Spanish colonists created institutions that served a small elite class at the expense of the country’s majority. Contrastingly, the United Kingdom gave its North American colonies more freedom. They often could self-govern, and economic development was encouraged by large numbers of British settlers. These divergent approaches to colonization created unstable institutions in Mexico and secure institutions in the United States, resulting in different levels of economic development today. This interpretation minimizes the effect of geography and culture on economic growth, instead focusing on the role of governance and political institutions.

Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson’s work places heavy importance on the utility of historical analysis in economic research. According to Acemoglu, the group used history “as a kind of lab,” combing historical case studies for evidence to shape their arguments. This represents a profound shift in the analysis of economic development. According to Dani Rodrik, an economics professor at Harvard, this research has propelled the study of history and national institutions to “the very center of economic analysis.” Last year’s winning research also highlighted the importance of historical developments in explaining current inequality. Claudia Goldin, the 2023 laureate, won the Prize for her work surrounding women’s participation in the labor force. She focused on how historical events shaped the labor opportunities available to women, ranging from the age of subsistence agriculture to modern innovations like contraceptive pills. Goldin proposes that changing societal expectations surrounding motherhood and the adoption of paid family leave programs among large firms have allowed more women to participate in the workforce, promoting the efficient use of a nation’s human capital.

Goldin, Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson’s work has significant implications. Not only has it influenced the way economists use history to study inequality, but it has also led to proposed solutions. This year’s winning research underscores the importance of inclusive institutions. Economies work best when a free market is balanced by stable, democratic governance and consistent, growth-oriented policy.

While Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson’s pro-democracy findings might seem a no-brainer, some economists have criticized their conclusions. Yuen Yuen Ang, a political science professor at Johns Hopkins, points to China, Singapore, and Taiwan as examples of states lacking inclusive institutions but still undergoing rapid economic development. In an article for The Conversation, University of Cambridge professor Jostein Hauge notes that more “inclusive” institutions are often defined by their conformity with long-held Western ideals of good governance. In making this assumption, Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson’s work may overlook non-western traditions of governance and policy-making that could benefit development in some nations. This criticism aligns with broader claims that the Nobel Prize disproportionately awards the work of European and American economists and unfairly emphasizes a Western perspective.

Acemoglu has responded to this criticism, acknowledging that democracy “is not a panacea” to economic inequality. In a news conference, he identified political polarization as a critical challenge that democracies face. This is especially relevant in the United States, long seen as the poster child for democratic government and strong economic development. Increasing political polarization and decreased satisfaction with the national government are top issues facing the United States this election season. Regardless of debates surrounding the candidates’ specific economic policies, the next president’s ability to unite different groups and maintain stable institutions will prove critical to continued economic growth.